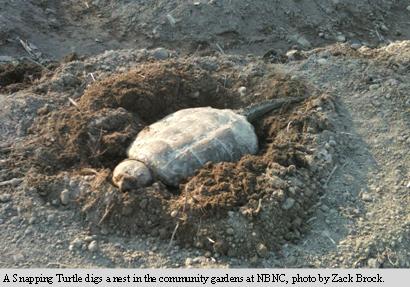

During these late-spring/early-summer months, Painted and Snapping Turtles leave the water in search of a place to lay their eggs. They favor open, sunny areas with loose, sandy soils to dig their nests. This preference often proves to their detriment, as roadsides, trails, and gardens often meet the turtles’ needs and cause them to come into conflict with people. Most turtles typically don’t travel far, but a female snapper is willing to travel over a half-mile in order to find a suitable nesting site.

If you come across a turtle, it is not advisable to relocate it to your favorite neighborhood pond down the road. What you can do is search for evidence of whether or not she has laid eggs (is she walking towards the water? away? Is she digging a hole? filling one?). If you’ve found evidence that she has already laid eggs, you can try bringing her back to the nearby wetland where she came from. If you don’t find any evidence that she has laid eggs, moving her will do little good as her instincts will drive her back to land to nest.

Moving Painted Turtles is fairly straightforward. Most will recoil as far into their shell as they can squeeze, but occasionally one may struggle and scratch at you with its claws. Rarely is any real damage inflicted. Snapping Turtles, however, live up to their namesake. In water they are quite docile, but on land their aggression is unmatched. Their powerful beak can clamp down with great force and speed, and their long necks give them a surprisingly long reach. There is no easy way to move a large snapper.

Carefully moving the turtle with a shovel may save you having to touch it, but if such a tool is unavailable, here are some other tips. Immobilizing the turtle by covering its head with a towel or other cloth may restrict its ability to snap at you. Never carry a turtle by the tail as it can cause injury. Instead, grab her with a hand on each side of her carapace (top shell) just above her hind legs. Be careful, as her neck is long and can snap backwards a considerable distance. Also beware that her claws are long and sharp, and without protective handware, she can easily draw blood.

Carefully moving the turtle with a shovel may save you having to touch it, but if such a tool is unavailable, here are some other tips. Immobilizing the turtle by covering its head with a towel or other cloth may restrict its ability to snap at you. Never carry a turtle by the tail as it can cause injury. Instead, grab her with a hand on each side of her carapace (top shell) just above her hind legs. Be careful, as her neck is long and can snap backwards a considerable distance. Also beware that her claws are long and sharp, and without protective handware, she can easily draw blood.When the turtle you encounter on land lays her eggs, you might find the location she has picked is not conducive to a successful breeding season. For example, the pile of woodchips next to the street tree nursery at NBNC was not a wise place for a female snapper in 2009. Her eggs would have dried up quickly in the woodchips and the pile would not have remained in that place throughout the summer. Ultimately, we decided the only way to prevent her nest from failing was to relocate the eggs.

Under the extreme circumstance that a nest needs relocation, look for a spot with good sun exposure, similar soil moisture (not too dry, not saturated), and bury the eggs at a similar depth. Some people believe it is best to keep the eggs the same side up while others are not convinced that it matters. Bare soil or just grass cover is good, but anything that will grow deep roots and provide shade is a bad idea.

Once a female has successfully laid her eggs, her role in their lives has ended. The threats the hatchlings will face are numerous, and they will have no parental supervision… just instinct. When discovered by raccoons, nests are quickly exhumed and eaten. Nests near human habitation are especially susceptible to this predation, as raccoons occur in greater densities in highly human-populated areas. If they are lucky enough to make it through the summer, a clutch of tiny, quarter-sized hatchlings will emerge from the soil in late fall, or early the next spring. In their first days, their shells are soft and malleable, offering little protection from predators. Some of the many creatures that could consume a baby turtle include crows, bullfrogs, bass, raccoons, otters, snakes, and countless others.

Next time you are out driving the streets, hiking the trails, or tending to the garden, and a turtle comes into view, don’t panic! Instead, enjoy the miraculous feat of nature at hand. Assess the situation and take action if warranted. Take some pictures and submit your sighting to the Vermont Reptile & Amphibian Atlas. And share your story with us, we’d love to hear about your turtle experience!

No comments:

Post a Comment