New England winters are notorious for being harsh, especially as winter lingers a bit longer than is often welcome in the beginning of March. But for those who appreciate birds, there are about a dozen types winged gems that wander from the north some winters and warm our hearts. One of these northern visitors that calls Vermont “south for the winter” is the Bohemian Waxwing.

The Cedar Waxwings grace our region year-round, but Bohemian Waxwings only occasionally wander to our reaches. Known as an ‘irruptive species’, some years Bohemians are numerous while others they are wholly absent. Their presence depends mostly on the availability of food in the boreal forests farther north. Their preferred winter diet consists mainly of berries and fruits, so if, for example, the Mountain Ash crop is weak in Canada one year, we may find a plethora of Bohemian Waxwings in our backyards.

Although they are quite similar to their southern cousins, Bohemian Waxwings are quite distinctive if you know what you are looking for. In sound they are quite similar, with the Bohemian having a more ‘musical’ sounding high-pitch tremolo than the fairly flat, mechanical high-pitch sound of the Cedar. This distinction, however, is subtle and distinguishing calls comes with practice. A key feature that sets the Bohemian Waxwing apart from the Cedar Waxwing is the rusty-brown undertail coverts. When viewed from below, this field mark is very apparent and the easiest way to distinguish the two. Bohemian Waxwings are slightly larger, but this field mark is only useful when the two species are side-by-side. The name waxwing is derived from the red tips of some wing feathers, which reminded early observers of sealing wax and these feathers can also help to distinguish these species. The Bohemian Waxwing has yellow and white in addition to the red on its wing-tips. Another more subtle field mark is the grayer belly of the Bohemians, but this can be quite subjective based on lighting and is better used as ‘supporting evidence’ of an ID rather than a sole characteristic to rely on.

Finding Bohemian Waxwings is a game of chance. Even in years when they are present, their nomadic nature makes them difficult to find predictably over a period of time. A huge flock might descend on a tree, pick every branch clean of berries, and then move on, never to return. They often seem to show up in downtowns, working the fruits of ornamental crabapple and cherry trees that line city streets. When they do this, the flock will often land atop a nearby tall tree which they’ll use as a ‘staging area’. Smaller groups from the flock descend upon the fruiting tree, swallowing entire fruits whole. When they go into this sort of feeding frenzy, they can often be approached fairly closely without being spooked. After all, in the remote northern regions where they breed, they may never encounter a single human so why perceive us as a threat on their wintering grounds?

I once observed a flock of Bohemian Waxwings 1,000 strong in the heart of Burlington. The typically soft, high-pitch trill blared throughout the two city blocks they filled along College Street. I quickly ran to a friend’s house down the road and dragged them out to see the commotion. These non-birders couldn’t help but smile with delight as we stood between the waxwings’ staging areas and the fruit trees from which they fed, birds buzzing within inches of our heads. While this flock was unusually large, they frequently gather in groups of 50 or more, sometimes attracting attention from creatures other than humans. While photographing a flock of Bohemian Waxwings outside my apartment in Winooski, the entire bunch abruptly took off. Despite my close proximity to them, my slow fluid movements must have spooked the flock. Or did they? As I turned my head, a Merlin sat on the ground, waxwing clenched in its talons, before flying off with its prey (pictured below). A study in South-central Saskatchewan found that Bohemian Waxwing accounted for over a quarter of Merlins’ diet!

While seemingly oblivious to the Merlin’s presence in this instance, Bohemian Waxwings can be quick to take notice of other predators. The soft chatter of a flock I observed in South Burlington stopped abruptly and all the waxwings struck a cryptic pose, bodies extended vertically and necks craned skyward (pictured right). As I mimicked the waxwings with my own posture, I quickly saw the cause for their change in behavior: a Northern Harrier passing high overhead.

In addition to attracting the attention of predators, there are inherent risks that come with a diet of fruit. Feeding on street corners means encounters with cars are inevitable, and Bohemian Waxwings can be susceptible to being hit. This fall, an injured Bohemian Waxwing was brought to NBNC from the statehouse lawn in Montpelier, the likely victim of a hit-and-run. In spring, different problems arise. Fruits that have managed to persist through the winter may have been host to a congress of yeast and sugars, resulting in fermentation. On one occasion in Winooski, I found a waxwing that lay helpless on the lawn incapable of flight. At first I suspected injury, perhaps from a cat (another major predator), but then I realized this waxwing was drunk! Waxwings aren’t the only creatures prone to inebriation, but their choice of food means an increased risk of succumbing to alcohol, sometimes fatally.

While you may witness waxwings’ misfortunes, the careful observer will also enjoy a host of other interesting behaviors and interactions. Waxwings are highly gregarious creatures that enjoy each others’ company. Their constant chatter is thought to strengthen cohesion of the flock, and intensifies prior to the waxwings’ movement from one location to another. Even though they breed hundreds of miles away, we get a glimpse into their summer lives as they begin pairing up as early as January. Amongst the waxwings repertoire of flirtatious displays are the “gifting” of fruits, feeding, and “billing” (touching or clasping of beaks). In a 1988 study, Cramp reported “…[a] male sidling up to perched female and hopping from one side of her to the other, billing, and hovering briefly in front of her to offer a fruit.”

Not only is the Bohemian Waxwing a bird worthy of adding to any “life list”, but anyone who ignores them after marking the Bohemian on their checklist is missing out. The next time you stumble upon a flock of Waxwings, spend some time with them and get to know them and you won’t be disappointed. Before you know it, spring will come you’ll be once again waiting for winter’s gems.

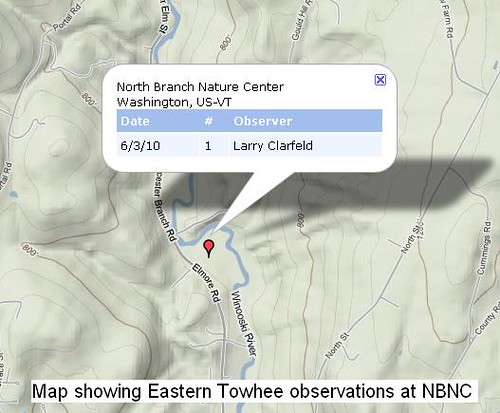

Essay and photos by Larry Clarfeld

It was a warm, spring evening in a small village in Vermont. Patches of snow littered the forest floor, and a slushy precipitation fell from the sky. A deafening chorus of peeps and croaks rang through the night. Little did the inhabitants of this village know, an epic journey was underway.

It was a warm, spring evening in a small village in Vermont. Patches of snow littered the forest floor, and a slushy precipitation fell from the sky. A deafening chorus of peeps and croaks rang through the night. Little did the inhabitants of this village know, an epic journey was underway.

While driving to work this week, a raven flew low over my car, carrying with it a sign of spring. The raven was holding a stick in its beak, which gave me hope that spring really is coming, despite the two feet of snow that fell just a couple of days prior. Although I quickly lost sight of the bird, I’m sure it was heading to a nest under construction somewhere nearby.

While driving to work this week, a raven flew low over my car, carrying with it a sign of spring. The raven was holding a stick in its beak, which gave me hope that spring really is coming, despite the two feet of snow that fell just a couple of days prior. Although I quickly lost sight of the bird, I’m sure it was heading to a nest under construction somewhere nearby.